We often talk about transport in a linear sense — how to best get from point A to point B. In the same manner, for many years our economies have existed as a linear construct, using materials from the earth to create a product that then gets thrown away as waste. That’s true of the transport industry as well. Private vehicles are produced to facilitate travel before being scrapped as waste at the end of their limited lifespan.

But what if we began to think differently and consider ways to transform transport and mobility using the principles of a circular economy? By minimizing resource consumption, lowering waste generation, and extending the life of products, the circular economy can greatly improve transport’s environmental balance and reduce CO2 emissions.

A central tenet in the European Green Deal, the circular economy when implemented in transport systems would see greater mobility using fewer vehicles that consist of more durable and easily reparable products. Circular mobility is clean, flexible, and shared. So, what’s holding back the transition? There are several myths floating around about what the circular economy would mean for transport so let’s clear them up:

Myth 1: With growth in both population and urbanization, we can’t reduce the number of vehicles on the road.

A circular mobility system centers on three principles: clean, flexible, and shared transport. While the number of vehicles on the road may remain consistent if everyone continues to drive privately, car-sharing plans can reduce the number of vehicles produced and along with it, limit the amount of natural resources drawn upon for new production. And with the total resource consumption of a passenger car averaging 70 tons of materials and resources and production generating around 10-11 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, there’s an issue of environmental depletion with each new car produced. Sharing can go one step further toward reducing the impact of vehicles on the world and congestion on the road.

Myth 2: Used vehicles and other products are already sufficiently recycled.

The World Economic Forum has warned against misconstruing the impact that recycling has had, noting that, “over the past 70 years a clear pattern has emerged of large polluters supporting efforts that look helpful in one respect, but are actually little more than distractions to real systems change.” Though theoretically, up to 99.5 percent of the materials used in vehicles can be recycled, one percent of the emissions produced by a vehicle are generated during the recycling process. True change requires not only recycling but also other aspects of the 9Rs strategy, including refuse and reduce.

Myth 3: The move to electric vehicles means we can all continue to drive private vehicles.

Electric vehicles go a long way toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the problem of congestion and the expansion of roadways does not get resolved if everyone continues to drive. Switching to active or sustainable mobility methods and moving to neighborhoods that allow for short-distance commutes with a strong work/live balance can free up that congested road space for parks and other green spaces. Not to mention the outstanding questions about the lifecycle of such vehicles and their subsequent waste.

Myth 4: The cost of transition is too high.

For the private consumer, trading out their private vehicle for a car sharing membership can reduce monthly costs tremendously. For cities interested in implementing more circular economy principles, the initial cost of developing a bus system or bicycle infrastructure will pay itself off over the long-term.

Myth 5: Adding road infrastructure for bicycles and buses will create more congestion in cities.

During the pandemic, many cities constructed temporary bike lanes on highly traveled roadways to ease the transition from public transit options to bicycles. Once cars returned, however, congestion grew in places like Bogota, Colombia, while Paris instituted new regulations on travel in the inner city to allow the bicyclists to keep their added space. Ensuring multi-modal transport does not worsen existent problems with congestion, which can be resolved through urban planning.

Myth 6: The 9R strategy isn’t viable for mobility over the long-term.

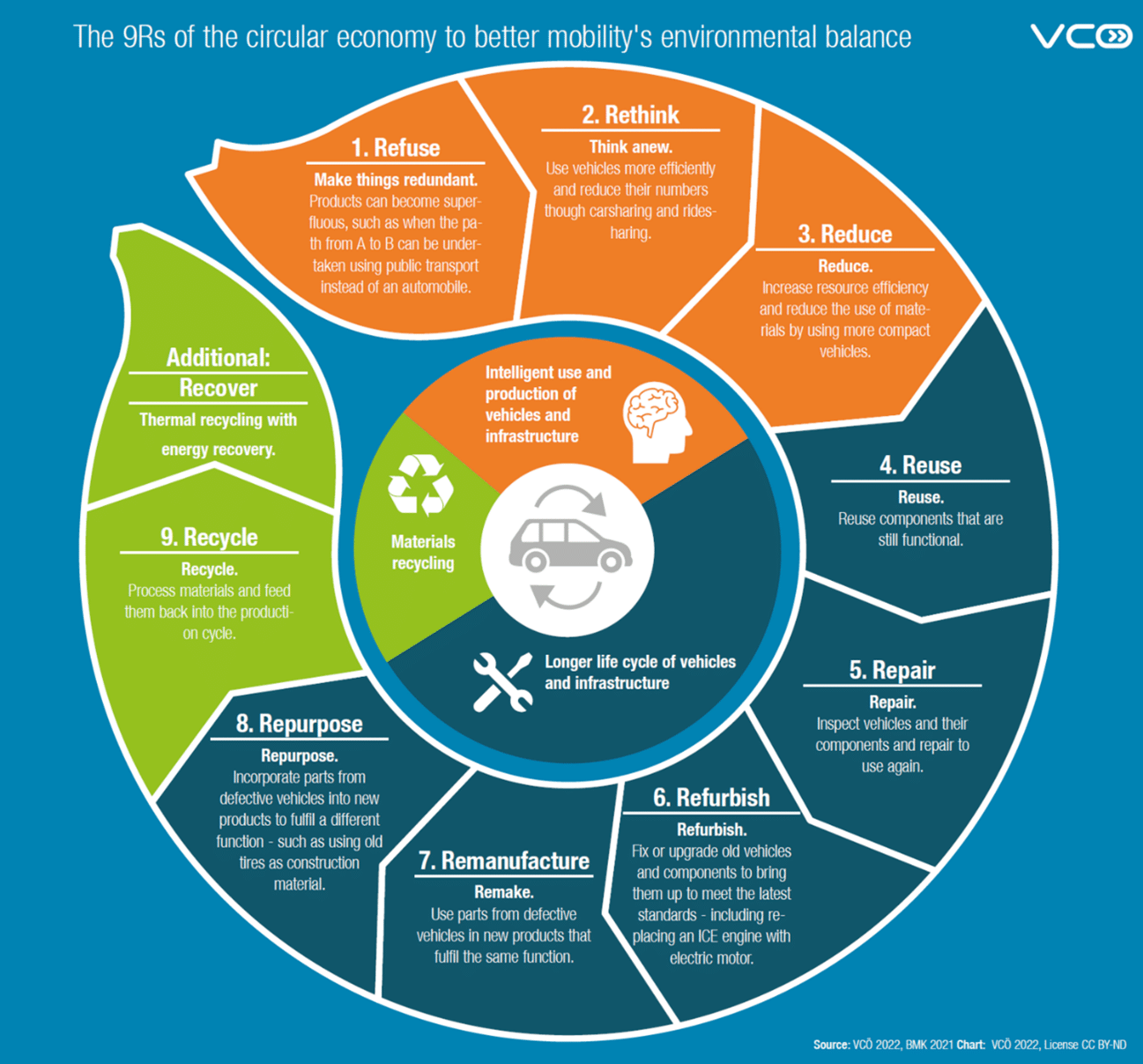

Refuse, rethink, reduce are three of the 9Rs that make up the principles of circular economies. While the initial move away from the status quo may feel difficult at first, the rethinking part of the strategy is clear. Mobility is dynamic and once the momentum grows, the circularity increases. The following infographic depicts how the 9R strategy for circular economy applies to mobility.

Myth 7: Circular economy principles slow growth.

Unfettered growth has relied on a throwaway attitude; the circular economy is a systems solution that requires an initial rethink that will create greater opportunities for growth once implemented.

Myth 8: No one wants to participate in the shared economy when it comes to vehicles.

The average private vehicle is at a standstill 95% of the time, with precious urban space devoted to parking lots and street spaces dedicated to housing an unmoving vehicle. While the sharing economy may take some adaptation of habits, it also alleviates the stress of finding parking, paying insurance, and managing repairs. While each person must weigh the pros and cons before making the choice for themselves, shared mobility has shown itself to be beneficial for many.

Myth 9: Adding more public transport in the form of buses will not reduce material use or air pollution.

Studies in Europe have revealed that on average, trips by private car contain just 1.5 passengers. A reduction in cars on the road by convincing people to switch to shared mobility like buses can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Further, air pollution can be reduced by the electrification of buses. By applying the principles of circular economy to e-mobility, material use can be minimized.

Myth 10: Mobility will not be accessible or affordable.

Circular mobility systems are defined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation as being multi-modal and shared, with accessible, affordable and effective means of transport. What that looks like is unique to each city, but low-cost systems are effective in getting people to switch to less polluting methods of transportation, as Germany’s reduced train fares program in the summer of 2022 showed.

Sources:

The 9R Framework of Circular Approaches with the production chain in order of priority.

The circular economy: how it can lead us on a path to real change

Implementing the circular economy in mobility