By Marta Pastukh, Mathias Merforth, Viktor Zagreba, Armin Wagner

Ukraine’s victory is not yet complete. Reconstruction is, however, already in full swing in many parts of the country – rightfully so. At the same time, the debate around the nature of that reconstruction, particularly how to design a green recovery, is growing. Though numerous papers have been published on green recovery in general and on certain sectors in particular, only a few discuss urban mobility.

When discussing urban mobility in Ukraine, we are referring to cities as well as to hromadas, or local municipalities. Access to mobility services in these areas is vital for both business and for the population. A resilient urban transport infrastructure is a fundamental precondition for the normal functioning of any city and urban economy. “Healing” the tremendous war damages wrought on public transport systems, urban roads, bridges and vehicle fleets is not only necessary to getting the Ukrainian economy back on track, but it could also trigger the rise of a new strategic sector with economic growth and employment opportunities, as we will later outline.

When discussing a green recovery of the country’s urban mobility, there are several points to keep in mind:

- In Ukraine, despite Russian aggression, considerable efforts are currently being made to keep the transport system running and modernize it at the same time. New and renovated vehicles, enhanced services and new roads are being completed even during the war. Innovative approaches such as cashless ticketing are also being pursued. Overall, the efforts of Ukrainian workers and decision-makers in the transport sector are very high and worthy of full recognition.

- In Ukraine — as in many other countries — urban transport has no proper place within national structures. While the Ministry of Infrastructure (MIU) is essentially concerned with large national infrastructure, the Ministry of Communities and Territories Development is more concerned with issues of local self-government. Cities thus maintain a great deal of ownership over urban transport issues and thus see greater opportunity – a positive thing that should not be undone. Yet these municipalities often lack appropriate governance structures and access to funding – which is even more true for medium-sized and small cities.1

- The green recovery debate is often difficult to operationalise. There is a need to translate often abstract, cross-cutting objectives into tangible, actionable steps and results. This holds true for the transport sector in general and urban mobility in particular.

- While the green recovery debate often focuses on individual technologies or solutions, a deep transformation requires a holistic approach that includes planning and policy approaches, institutional amendments and changes in legislation, financing, standards, and technical recommendations.

A clear intensification of the professional and public discussion on urban transport has been observed over the last ten years in Ukraine, especially in regard to public transport and cycling. While the debate over the future of Ukrainian cities remains ongoing, it has taken on both new dimensions and momentum due to the dynamics of the war. The fate of classic industries (steel, coal, ores…) must also be taken into consideration as part of this debate. Facilities are often damaged, and the question of the reconstruction’s meaningfulness stands unanswered. What comparative advantages can Ukraine leverage in other fields, such as know-how, (information) technology, the private sectors’ ingenuity? Will a sustainable transport industry become one of the new (green) pillars of the economy?

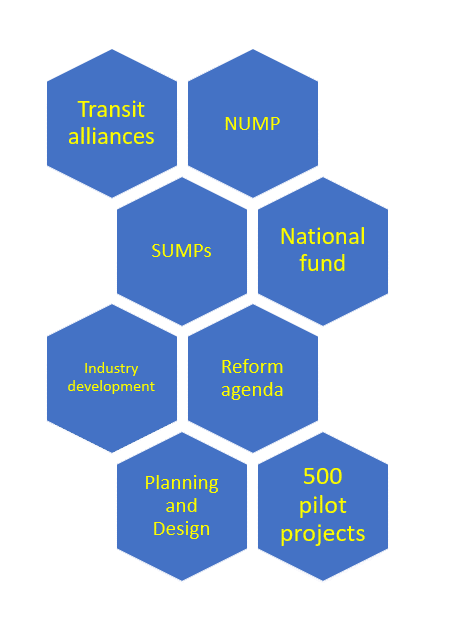

Against this backdrop, this paper outlines eight essential building blocks for a green recovery in urban mobility as part of broad reform agenda in Ukraine. By implementing the suggestions in this proposal, Ukraine and its international partners will reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, greenhouse gas emissions, and the number of people killed in vehicle-related accidents – while constantly improving quality of life. Citizens, businesses, and the government would all benefit from a shift towards more sustainable (urban) mobility systems.

The eight building blocks interconnect and reinforce each other as they form the foundation for a sustainable development of urban mobility. In a sense, they shape the institutional and administrative framework required for the further development of urban mobility in Ukraine.

Our eight building blocks in detail:

1. National Urban Mobility Policy Programme (NUMP): Develop visions and goals at the national level

While the planning and development of sound urban mobility systems is the responsibility of local governments in most countries, many nations will recognise that urban mobility is not merely a local concern. Considering urban mobility a topic of national interest is important in Ukraine, where almost 70 % of people live in cities. Cities are the centres of economic growth and individual advancement; they are also places that face the negative impacts of mobility, including high emissions.

To reflect on these challenges and align urban transport planning and policymaking in (all) Ukrainian cities with the Lugano principles and European perspectives, we propose developing a National Urban Mobility Policy and Investment Programme (NUMP). A NUMP is defined as a strategic, action-oriented framework for urban mobility to enhance the capability of Ukrainian cities to plan, finance and implement projects and measures designed to fulfil the mobility needs of people and businesses in cities and their surrounding areas in a sustainable manner. It builds on existing policies and regulations and is aimed at harmonizing relevant laws, norms, sector strategies, investment and support programs towards an integrated approach for the benefit of cities and their inhabitants. It takes due consideration of participation and evaluation principles.

A NUMP can be a useful process for facilitating a more coordinated approach to urban mobility policy, planning and investment. Understanding the link between what takes place at the national and at the city level and designing a framework that allows efficient coordination and effective support from the national to the city level is crucial to improving investment conditions and bringing urban mobility systems on to a sustainable and low carbon track.

Source: National Urban Mobility Policies and Investment Programmes (NUMP) Guidelines

We propose a four-phase approach to develop the National Urban Mobility Policy2:

The development of a Ukrainian NUMP must reflect the Lugano Principles; it should not only anticipate but also actively support key directional economic development decisions, such as a focus on digitalisation and higher value creation in the country, through, i.e., renewable energy production, smart electric components, vehicle/bus/tram production, battery production.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Communities and Territories Development and the Ministry of Infrastructure can take the lead here and facilitate an exchange among cities as well as the formulation of a NUMP. It is important to emphasise that in line with the subsidiarity principle, the defined goals and visions for Ukrainian cities are recommendations only and should not be regarded as prescriptive. Cities and hromadas shall remain in the driver’s seat in respect to urban mobility.

KPI:

- Key Performance Indicator (KPI): A National Urban Mobility Policy and Investment Programme has been adopted, together with an implementation programme.

2. Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning: Reforming and strengthening local responsibilities and planning processes, involving the public

At the local level, mobility goals are as diverse as the Ukrainian cities themselves. In the past, those defined goals often involved, whether implicitly or explicitly, the expansion of the road area, faster speeds, and a more rigorous separation between the various forms of transportation. More recently, however, cities such as Lviv, Vinnitsa, and Zhytomyr have begun to intensively address the issue of sustainability in transport. This is in line with a paradigm shift in the goals of mobility planning currently under way at the international level, where mobility no longer solely concerns the free flow of traffic. Instead, mobility planning ensures access to services, residential areas, work centres, leisure and cultural amenities; it is about managing mobility in a socially equitable, environmentally compatible way.

Modern mobility needs integrative planning approaches which satisfy the mobility needs of people and businesses in cities and their surroundings in a sustainable and inclusive manner. In order to improve planning and policy processes, the use of traffic planning methodologies and models based on regular and systematic surveys of mobility behaviour and the monitoring of actual traffic volumes must be mandatory. Data collection and management as well as the use of these data to forecast mobility behaviour and analyse the impacts of social trends, of investment projects in the mobility sector and of policymaking, are key on the path towards rational mobility planning. It must be born in mind, however, that models and plans only identify potential impacts. Defining the starting conditions, outlining the assumptions made, and evaluating the results are matters for planners and decision-makers to consider in close consultation with the general public. In the context of the ongoing war, an update of (local) transport models is needed that reflects a) the impact of war and b) new strategic priorities (Lugano principles etc; derivation of macroeconomic perspectives etc).

Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs) at the local level are strategic plans designed to satisfy the mobility needs of people and businesses in cities and their surroundings in a sustainable and inclusive manner.

SUMPs aim to create an integrated, green, accessible, and affordable mobility infrastructure that moves citizens and goods in a sustainable and inclusive way locally, while globally reducing transport-related GHG emissions. With comprehensive diagnosis and monitoring components, the SUMP provides a sound data baseline to the city, essential for a) evidence-based decision-making and b) leveraging investments for sustainable mobility infrastructure. The multi-stakeholder approach taken by the SUMP also strengthens the cooperation between and participation of different stakeholders and interest groups, leading to higher acceptance and ownership of the proposed measures.

The elaboration of a SUMP is structured along a standardised and widely tested process, called the SUMP-Cycle. The SUMP-Cycle itself is organised in 4 phases and 12 steps:

Source: SUMP learning programme for mobility practitioners

In terms of the policy and planning framework for mobility planning, the merging of administrative bodies and establishment of an appropriate hierarchical structure have a key role to play. The creation of effective mobility departments responsible for all aspects of mobility planning in Ukrainian cities will be a major step forward. These departments will also bear a high degree of responsibility for planning outcomes. The terms of reference of these mobility departments will comprise:

- Planning mobility, transport infrastructure and transport services;

- Traffic management;

- Construction of transport infrastructure;

- Quality monitoring.

This means that the departments responsible for planning and delivering mobility services will also be in a position to influence and manage the underlying causes of mobility trends, e.g. land use, the development of commercial and industrial sites, suburbanisation trends, and so on.

Specifically, we suggest encouraging Ukrainian cities to take up the SUMP concept and to make it a (mandatory) prerequisite for investments and decision-making in urban transport as well as to set up appropriate and effective mobility departments.

Box:

Source: Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan for Lviv

Example Lviv: The city of Lviv developed a SUMP that was formally approved in 2018. The SUMP process supported awareness-raising measures for deputies, decision-makers and district administrations. All stakeholders agreed that the pedestrian as well as public transport should be prioritised at the top of the mobility pyramid (an inverted structure); that facilitated the decision to create separate lanes for PT and trolleybuses. It has become easier to justify projects to international organisations (EIB, GAP Fund…) when they are included in the SUMP. At the institutional level, the SUMP process addressed a lack of Institutionalisation; a significant change came with the establishment of a new department for urban mobility and street infrastructure. Prior to that, the transport office was under the domain of the Department for Housing.

- KPI: Planning procedures are in line with international standards (e.g. SUMP guidelines) and facilitate adequate public consultation.

3. Strengthening and integrating local public transport systems

The last few years have shown a variety of innovative approaches to strengthening public transport in Ukrainian cities: new vehicles, new ticketing systems, new routes. As convenience still lags far behind that of private cars, however, attracting “choice riders” has not proven very realistic and the funding gap remains substantial.

The public transport companies’ often poor financial status is caused by a mixture of factors – a precarious revenue situation, low fares, a significant proportion of passengers entitled to free travel, unreliable payment of equalisation contributions by the state, and the general expectation that public transport prices will remain low even though local public transport is supposed to be profitable. Further, the full integration of “Marshrutka”-services has not yet been achieved.

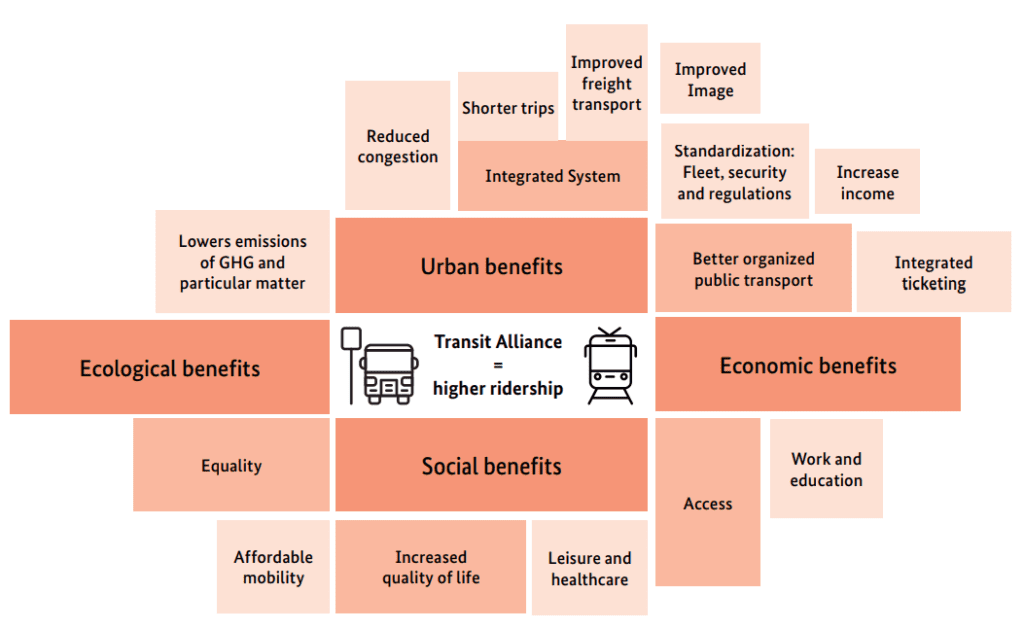

Source: iNUA #5: Transit Alliances

The technical means for change are quite clear: new rolling stock, new tracks, dedicated lanes, new ticketing systems etc. However, from a green recovery perspective, in order to substantially strengthen public transport, the institutional dimensions need to be addressed:

Internationally, a three-tier structure has proven its worth by defining the general objectives for local public transport, clarifying who defines the quality of services, who is responsible for service provision and pricing, and who monitors and pays for the services provided:

- Local authorities (cities, hromadas, oblasts etc.) define the policy framework (goals) for public transport;

- The management level is a non-commercial entity which defines, purchases, supervises and pays for transport services (financial management);

- Bus and rail operators are contracted to deliver services.

This three-tier approach to local public transport service delivery must be strengthened in Ukraine as well. Here, corporate decisions (tariffs and pricing structures, also in relation to season tickets) must be shifted to tiers 2 and 3. Tier 2 should also deal with the integration of offers from various municipal and private operators relating to tariffs, tickets, timetables and types of service.

This concept corresponds to the idea of transit alliances. Transit Alliances can be understood as an umbrella for public transport in the form of a legal entity, administrative unit or association which aims to integrate all public transport services and modes in a city, metropolitan area or wider region into one attractive and easy-to-use system with major benefits for users. Individual operators may still keep their independent status.

In the Ukrainian context, it may make sense to establish transit alliances starting from the oblast capitals and integrating functional transport areas of the surrounding hromadas. Whole oblasts or larger functional units can be included. With a view to digital possibilities, it also seems conceivable to skip the level of transport associations and introduce a Ukraine-wide fare and ticketing system comparable to the discussions underway in Germany in regards to a successor to the 2022 flat rate tariff of 9 Euros per month.

- KPI: The framework conditions for local public transport have been improved and clear structures established. (Transit alliances established)

4. Innovation campaign – launch 500 projects for shared learning

Internationally, a tremendous shift towards smart mobility solutions is underway. Many of those solutions have already arrived in Ukrainian cities; a more ambitious roll-out can help to fast-track the uptake of sustainable mobility.

We propose launching a national innovation and upscaling programme, “New Ukraine – new mobility,” focusing on the following 5 thematic areas, covering e.g.:

- Transport Demand Management: High-quality public transport (e.g. Bus Rapid Transit, trams), parking management, congestion charges, road tolls

- Livable cities: barrier-free spaces, street calming, cycling infrastructure, low-emission zones, upgrading of public space

- Climate-transformative mobility: electric mobility, integration renewable energies

- Smart mobility: carsharing, bike-sharing, micromobility, digital solutions

- Transparent governance in mobility: civic participation mechanisms (e.g. cycling working groups, civic participation strategies for SUMP, smart authorities, transparent funding, citizen projects)

This pilot programme should encourage cities to propose and implement sustainability-oriented reform projects in the thematic areas listed above, with particular emphasis on the use of renewable resources, the mobilisation of domestic Ukrainian resources and know-how.

To evaluate the proposals and monitor their implementation, we propose establishing a Secretariat. Funding can be provided by the National Fund for Sustainable Urban Mobility, as described below. Foreign donors are invited to participate by providing funding but especially by sharing their experience.

The Secretariat should develop an intensive programme of seminars, publications and media-oriented activities in order to promote the rapid dissemination of knowledge, information and experience, to identify and — where possible — remove obstacles, and to promote broad participation by institutional and social stakeholders.

- KPI: The ‘Sustainable Ukraine – Sustainable Mobility” (Стійка Україна – стійка мобільність) is established and is being implemented in 500 projects in Ukrainian cities and hromadas.

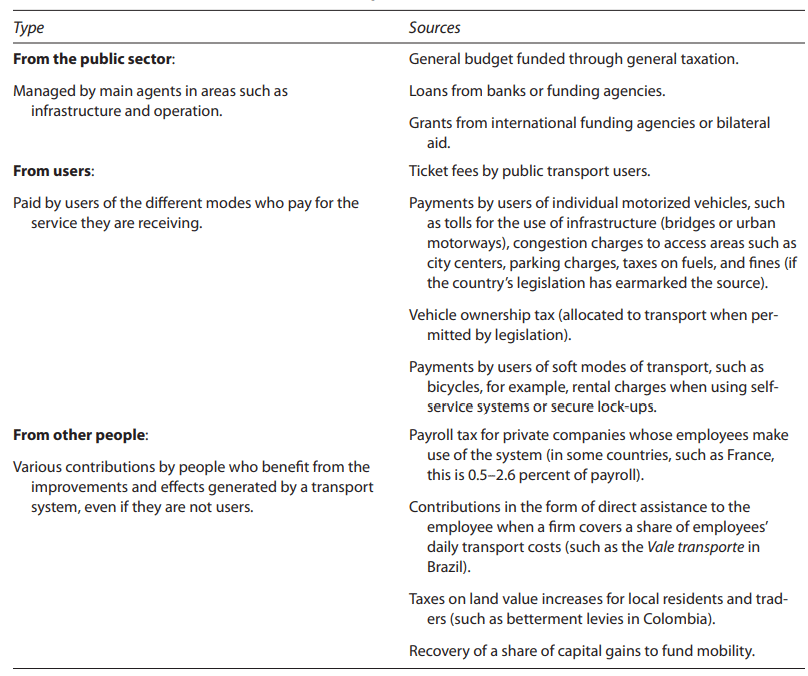

5. Securing funding

Lack of funding is a serious problem for mobility policy in Ukraine. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge in frank and realistic terms that – before the war – mobility in Ukraine was relatively cheap. Fuel prices were low in comparison to the rest of Europe, tariffs in municipal and national public transport were also low and there are very few other mechanisms for refinancing the sector through taxes or levies.

It is essential in the Ukrainian mobility sector to further develop the concept of user financing as well as complementary funding – differentiated by investments and recurring needs for service and maintenance. The table indicates potential sources of funding:

Source: Sustainable Urban Transport Financing from the Sidewalk to the Subway (worldbank.org)

Further, the internalisation of negative external effects (congestion, air pollution, traffic accidents, climate change) should be a principle for financing of transport.

Good local public transport should not have to cover its own costs. State and municipal subsidies for local public transport are commonly provided in other countries and justified by the high socio-economic benefits (e.g. accessibility of workforce to workplaces, reduced noise, emissions, and resource consumption, accident prevention, etc.). It is important that the benefits of subsidising these services are clear and transparent and reflected in increased user figures.

An effective instrument in this context could be the establishment a National Fund for Sustainable Urban Mobility. This could potentially draw on experiences or be linked to the national road fund, replenished by increasing fuel taxes on petrol and diesel by an amount of x UAH/litre (to be defined) or based on the vehicle registration tax. This fund can also be linked to the ongoing discussions around a new Marshall Fund or similar efforts. It is important to emphasise that in line with the subsidiarity principle, political responsibility for funding and financial prioritization should lie with the cities. Cities and hromadas shall remain in the driver’s seat in respect to urban mobility.

Cooperation on this issue should be initiated between the Ministry of Finance, the Ukrainian Ministry of Territories and Communities Development and the Ministry for Infrastructure.

- KPI: A National Fund for Sustainable Urban Mobility is established.

6. Urban planning reform. Separate, mix, prioritise, redefine speed

Planning and design in Ukraine are still strongly influenced by the “old school” approach that does not reflect best EU practices. For instance, the cities still develop and update so-called Genplans, and those are developed by one of several “Research institutes” based in Kyiv, even for small cities somewhere in the country – reflecting planning approaches from 40-50 years ago. As for modern practices, only up to ten cities of Ukraine, out of about 450 cities in total, have developed SUMPs, even though this document doesn’t have any official recognition in the national legislation. Similarly, the detailed planning and design stage for a street or square, is not required and not recommended by national norms, and therefore, it is only applied by very few cities. All others get directly master planning to detailed engineering and construction. As a result, cities spend taxpayers’ money on projects that are car-centric, unsafe, overly expensive and not sustainable. Some projects are complete failure and cannot even be finished over years and years. Examples are two bridges, in Kyiv and Ivano-Frankivsk, that can become textbook examples of lack of planning.

The focus must therefore shift in future to a) more careful and participatory planning and design approaches and b) focusing on mobility management with clearly defined usage priorities. Mixed traffic should become the norm, especially in city centres and residential areas. A very close link between spatial development and mobility needs to be established.

Prioritisation must be made based on the economic, social and environmental impacts of mobility forms and following a hierarchical sequence, e.g. (compare box SUMP Lviv):

- Walking

- Public transport (on major arteries and in area development)

- Cycling

- Use of public spaces

- Delivery and public service vehicles

- Free-flowing general traffic

- Stationary traffic (parked vehicles).

A need for reform also arises in relation to the adaptation of the national standards – DBN and DSTU – to new technical developments in the fields of vehicle manufacturing, road construction and technology. We recommend launching a comprehensive and science-based reform of those standards.

A strong focus must be placed on the broader use of the possibilities of the DBN in the concrete design of new streets – i.e. the positive exploitation in terms of sustainable mobility. At the same time, it should be encouraged that the reconstruction of municipal streets and public space is based on elaborate planning processes, that involve public participation and competition between street designers. The planning and detailed design stage is often missing in Ukraine’s infrastrcutrure development practices, and this need to be changed. To this end, local decision-makers, technical staff and consultants should be empowered to apply faster and more ambitious innovative and safe designs for mobility – here, systematic capacity building should be fostered.

- KPI: Technical standards as well as planning and design approaches been thoroughly revised, facilitating the construction and use of sustainable mobility modes.

7. Sustainable transport industries as building block of the new Ukrainian economy

Bringing the tram, trolley bus and metro systems in 45 Ukrainian cities (including those under temporary Russian occupation) along with urban infrastructure in general to modern operational standards creates an enormous opportunity for vehicle and equipment manufacturers in Ukraine and the Ukrainian economy as a whole. Expanding Ukraine’s capacities as a producer of locomotives, railway coaches, buses, trams and electric supplies such as batteries or cables will not only be urgently required to maintain and increase capacities of the Ukrainian mobility sector, but it will also help position Ukraine as production hub ready for European and global markets.

Sustainable transport industries comprise in particular:

- Rolling stock: manufacturers, designers, suppliers of vehicles and components (e-buses, trams, passenger train cars, locomotives, utility vehicles, cargo-bikes, etc.),

- Infrastructure components: manufacturers, engineering and construction firms for railroad, tram, trolleybus and battery-electric bus systems, battery, cable industry, substations, signaling and other equipment,

- Digital IT solutions for transport systems: e.g. specialised IT solutions for railway systems, public transport operational and energy management, electronic ticketing and information systems,

- Sustainable mobility business: other areas that would benefit from a green recovery (e.g. consultancy and IT businesses, car-/bike-sharing, bike tourism).

We recommend developing an Urban Mobility Industry & Investment Strategy to provide a comprehensive overview of investment options for the production of sustainable mobility vehicles, supplies and infrastructure in Ukraine for domestic and international clients.

This approach supports economic growth, transforming the economy as well as creating modern jobs.

- KPI: An Urban Mobility Industry & Investment Strategy is developed.

8. Ongoing reform and adaptation: regulatory reform – upgrading skills – international networking

A green recovery approach offers the opportunity to speed up previously initiated reforms, to reform comprehensively as well as ambitiously and in line with European practices and objectives.

In order to clarify the status quo and potential demand, we propose that a more detailed analysis of the quantitative and qualitative need for reform be carried out. This should involve systematic analysis of the following topics, with benchmarking against the best European standards in each case:

- The DBN/DSTU (see chapter VI) standards and their revision over recent decades

- The legislative basis

- Road traffic law and regulations

- Academic curricula and the separation between training and research institutions, which still exists in some cases

- The level of academic and public debate

- Skills upgrading for municipal staff in relevant fields of work

- Quality of professional organisations and alumni networks in the mobility sector

- International networking and participation in international projects

As part of the identified reform needs, the national government shall be encouraged to open the legislative possibility for cities to introduce 30km/h zones as well as low emissions zones (LEZs).

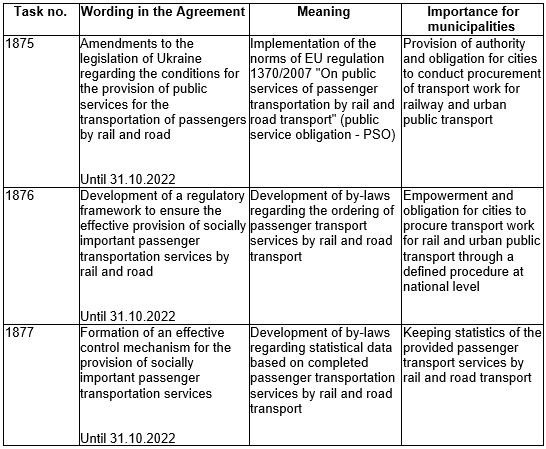

Ukraine is a signatory of the Association Agreement with the EU. For its implementation, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine on October 25, 2017 with Resolution No. 1106 approved the “Plan of measures for the implementation of the Association Agreement”.

The plan contains more than 120 tasks in the field of transport, most of which relate to legal and economic regulation in the sector of rail transport, aviation, sea, and river traffic. Just three tasks concern urban public transport, and the government has not delivered on this commitment yet.

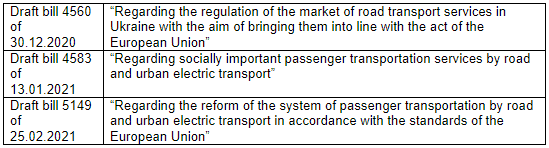

To implement those tasks, the Verhkhovna Rada needs to return to work on the three draft laws, that were submitted in 2020 and early 2022:

The National Transport Strategy of Ukraine

The document was adopted in May 2018, and an Implementation Plan to it was adopted three years later, in April 2021. Both documents are large in scope and scale, and have at least 17 mentions of sustainable mobility-oriented actions that are in line with EU Green Deal.

Examples of the tasks in the Implementation Plan, that would have positive impact on advancing sustainable urban mobility, include:

- Task 55. Public transport tariff regulation reform in line with EU norms and practices

- Task 86. Shift towards electric vehicles in urban public transport

- Task 118. Traffic safety measures, Improvement of pedestrian and development of cycling infrastructure

- Task 145. Shift of passengers and shipments from roads to rails and waterways

- Task 147. E-vehicles, e-public transport and bike sharing

- Task 148. Reduction if emissions from public transport

- Task 160. Modern public transport

- Task 164. Multimodality and single ticket

The Government was supposed to publish a progress report on the first year of the Implementation Plan in March 2022, but did not do so due to the War. Have many of those self-committed tasks been implemented by Ukraine? From public sources we can say that not. Should they be implemented? Definitely, yes. They have not become less important due to the war.

An observatory can be used to monitor progress, address short-term staffing needs, and ensure appropriate communication.

- KPI: A comprehensive reform programme for urban mobility planning and implementation is established and continuously monitored.

Summary

The above building blocks do not, by any means, constitute a comprehensive overview of all the challenges related to sustainable mobility in Ukrainian cities in a post-war period. Other topical aspects such as poor traffic safety, corruption, inadequate statistics, lack of city logistics strategies, and the absence of parking management are not discussed here. The aim is to present overarching building blocks which will help to provide a framework for future-oriented decision-making.

Decisions for or against individual approaches and priorities within the individual areas will influence mobility in Ukrainian cities in the coming decades. Before any decisions are taken, it is essential to weigh up whether, directly or indirectly, the measure makes individual car use more attractive or whether it promotes walking, cycling and local public transport. Is the decision in line with the old or the new paradigm? This will determine what the future holds – will it consist of gridlock, or will mobility be diverse, attractive and affordable, with few negative impacts? The policy course will be established in the next few years.

It is clear that there are no black-and-white solutions, panaceas or low-cost quick wins. Success will only come from ongoing and systematic conceptual development and the positive intellectual conflict of ideas.

Sources:

- The Urban Transport Sector in Ukraine – A baseline report in the context of the War of 2022 and prospects for a cgreen post-war recovery of Ukraine (Viktor Zagreba, Demayn Danylyuk) Prepared by Oresund LLC, Ukraine at the assignment of the European Climate Foundation. October 2022. (forthcoming)

- Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP) Toolkit

- SUMP learning programme for mobility practitioners

- National Urban Mobility Policies and Investment Programmes (NUMP) Toolkit

- UKRAINE – RAPID DAMAGE AND NEEDS ASSESSMENT“ (World Bank, Ukrainian Government, EU)

- Sustainable Urban Transport – Financing from the Sidewalk to the Subway; Capital, Operations, and Maintenance Financing (Arturo Ardila-Gomez and Adriana Ortegon-Sanchez)

- Urban Mobility in Ukraine: The 13 billion Euro gap – The next decade’s reform and investment needs (Mathias Merforth, prepared by GIZ-SUTP), April 2014

Feel free to comment, amend and add – feedback via: armin.wagner@giz.de