A blog on how mobility becomes a lifeline for connecting with others, political participation and planning future activities – providing a sense of agency in a situation of displacement, written by Emma Lehbib, a young German woman with roots in Western Sahara.

© Xurxo Lobato via Canva.com

Every weekday, a bus departs from Ausred to Rabouni at 7 AM, a 20-minute ride that plays a crucial role in the lives of individuals like Aisha Alien. It is the only bus that departs from Ausred. If Aisha or her peers do not catch the bus, they will have to opt for a taxi – a more expensive option that would cost a third of her daily wage. Walking in the scorching desert for such long distances is not an alternative. A social studies teacher and an executive member of the Sakia El Hamra and Wadi El Dahab Students Union, Aisha’s story reflects the broader challenges and significance of mobility in the Sahrawi refugee camps.

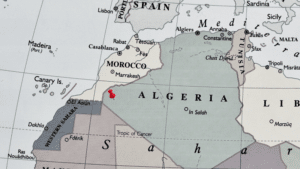

The Sahrawi refugee camps are in West Algeria in relative proximity to Western Sahara (see red pin).

Aisha is one of many who experience daily mobility challenges in accessing the Sahrawi Refugee Camps; and would benefit greatly from flexible and comfortable mobility services. Lowering the threshold to accessing mobility services can dignify and empower the residents and provide much needed access to basic services and political and cultural activities. To address these challenges, there needs to be a better understanding of these camps, how they came to be, and what they are now.

Understanding the Context

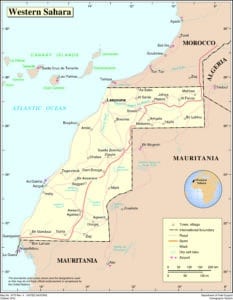

Aisha, born and raised in the Sahrawi refugee camps, is part of a community that has faced displacement since 1975. The Sahrawi are the people of Western Sahara, who were colonized by Spain for close to a century. With growing international and internal pressure, Spain announced its withdrawal from the territory in 1975. Morocco has long made claims over the land based on alleged historical ties of sovereignty over the territory. These were dismissed by the International Court of Justice in 1975, emphasizing the Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination. Still, Morocco invaded Western Sahara in the same year leading to an armed conflict between Morocco and the Polisario, the Sahrawi liberation movement. Despite a ceasefire in 1991, a promised referendum has not occurred, leaving a big part of the Sahrawi population in refugee camps near Tindouf, Algeria.

Official United Nations Map illustrating the occupied (on the left) and liberated territory (on the right) divided by a berm. © United Nations

Today, around 170,000 Sahrawis live in five camps, also referred to as Wilayas (Arabic for province), each named after a city in Western Sahara. These Wilayas are then divided into six Dairas (Arabic for district) which each consist of four Barrios (Spanish for neighbourhood). These units form a vast network and reflect the sheer size of the camps. The population density in each Wilaya ranges from around 60,000 to 15,000, with Smara being the biggest and Boujdour the smallest Wilaya. A particularity of the Sahrawi refugee camps is, that they are self-organized. Usually, international organizations or host states will administer the camps, here it is the Sahrawis themselves under the leadership of Polisario. In the Wilaya Rabouni, most ministries are situated, and it serves as the administration hub. There are no residential buildings, hence, all officials and employed workers commute daily or weekly to Rabouni. With some distances exceeding 150 km between Wilayas, reliable transportation becomes paramount.

Each of the Sahrawi Refugee Camp are structured in different sub-units which each consits of lower units. The distances between the camps range from around 15 to 150 km.

Challenges and Significance of Mobility

The need for sustainable and reliant transport services is critical in the Sahrawi refugee camps as it allows residents to collect humanitarian aid rations, access markets and health facilities, visit family, and nurture social connections. The Ministry of Transport of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (proclaimed state by Polisario) is responsible for transportation services within the camps. It has developed a relatively reliable transport system despite, limited resources and the adverse circumstances of desert terrain and weather. Several transportation methods, such as walking, shuttle buses, bicycles, use of private cars, carpooling, taxi services and donkey-drawn carts, play essential roles.

Residents most often walk for their daily activities, which encompass education, work, pharmacy visits, and market access, often conveniently clustered within the same Dayra or Barrio. Walking, however, becomes challenging especially in the summer, when temperatures reachup to 50 degrees. To facilitate group transportation and connect the camp to the adminstration hub that is Rabouni, a shuttle bus operates with scheduled rides during mornings and afternoons. While private cars or taxis are utilized, their availability is limited due to financial constraints. A more economical alternative is carpooling. Each Wilaya has meeting points, where the costs of the ride are shared by the number of seats filled.

Still, the costs of motorized transport modes must be emphasized. The camps exist for humanitarian reasons and hence, have no thriving economy. Residents receive rations of essential goods regularly and are financially compensated with symbolic rewards for their community engagement as teachers, nurses or in other professions. The possibility of saving enough money beyond basic needs is rare.

Private cars with Sahrawi registration plates indicating Wilaya of origin in front of a photo retail store in Rabouni. © Emma Lehbib

Bicycles, usually gifted to children by visiting foreigners, provide an efficient means of personal transportation – typically used in leisure time. In the absence of motorized vehicles, donkey-drawn carts prove invaluable for transporting goods and individuals, particularly for heavier loads or those loads that are unable to be carried for long distances on foot.

The challenging desert conditions, characterized by high temperatures, intense sunlight, and demanding terrain filled with sand and stones, exacerbate the physical demands of mobility. Climate change has heightened the conditions in the camps, extreme heat and heavy rainfalls have destroyed the housing of many in the camps. Aisha, a resident, acknowledges the hefty toll of transportation costs on her well-being, particularly when financial resources are scarce.

“Transportation within the camps is also considered important but negatively affects public well-being as it consumes money that is not available in our time.”

Aisha Alien

Mobility as a means of empowerment

For Aisha, mobility is key for her political activities in Rabouni, where the ministries’ headquarters and administration sit and serves as a hub for important activities and planning sessions. At the moment, her student union wants to create a library collecting research and studies on Western Sahara. Further, she wants to develop workshops for students and youth, and display mobile cultural exhibitions providing unique insights into the Sahrawi community and their history. In her profession as a social studies teacher, her teachings revolve around the history of her home country. It is a tribute to her ancestors and her struggle and serves to teach the next generations about their origins. Despite the challenging conditions of refugee camps, Aisha’s ability to actively engage in her community is empowering.

National Desert Tent Day celebration planned by the Sahrawi student union. Aisha (on the left) is preparing Sahrawi tea.

Living in refugee camps, kilometres away from their home country, Aisha’s generation has never seen their origins. Today, her father’s hometown, La Guera, is a ghost town. With their commitment to knowledge sharing and cultural practices, the Sahrawi resistance persists. The camps are also referred to as a place of dignity for the residents. Here, they face no fear of being persecuted for being politically active Sahrawis compared to their family members and friends that live in the occupied part of Western Sahara.

“The camps are safe.”

Aisha Alien

In the camps, Sahrawis being a nomadic population reside in tents called Khaymas, but also in adobe houses and cement-brick houses. Facing extreme heat and rainfall, the residents have been opting for more resistant housing options. © Xurxo Lobato via Canva.com

Mobility becomes a lifeline for political participation, connecting with others, and planning future activities – providing a sense of agency in a situation of displacement.

Why Mobility Services Cannot be Ignored in Refugee Camps

Refugee camps, initially conceived as temporary solutions to humanitarian and political crises, are meant to be transitional. The Sahrawis are reluctant to settle permanently in a foreign country and establish fixed infrastructure. The preference is often for temporary and mobile solutions.

“There are two groups of people in the camps: the ones who don’t want to establish anything that could even look permanent and the others who want to make their stay in the camps as comfortable as possible.”

Taleb Brahim (Quote from Manuel Herz’s book FROM CAMP TO CITY Refugee Camps in Western Sahara)

However, due to the unresolved and prolonged nature of many refugee situations, camps have started to urbanize and evolve into real settlements, some integrating with the local population through activities like intermarriage.

Organizations like UN-Habitat advocate for development programs in certain refugee camps, which usually rely solely on humanitarian aid. For these situations, durable solutions are preferred. This arguably unorthodox development depends on the political will of the host nations, position of the surrounding local population and of course the wishes of the refugees. It’s essential to always consider the diverse wishes and circumstances of the camp population.

For instance, the Dadaab Regeneration Strategy, published by UN Habitat in November 2023 for Garissa County, Kenya, aims to bolster self-reliance for both refugees and hosting communities. A key element of this strategy involves developing frameworks that prioritize accessibility and connectivity, including the establishment of a dependable transport system. According to UN Habitat, “[e]fficient connectivity and accessibility can ensure community well-being as well as provide opportunities for economic and social development and will enable the transition away from the traditional model of humanitarian camps to the new model of integrated settlements.” (Dadaab Regeneration Strategy). The overarching goals include the creation of an affordable and user-friendly public transport system, along with the enhancement of non-motorised transport (NMT) alternatives like walking and cycling, within and interconnecting settlements.

It is crucial to avoid characterizing refugees as a homogenous group and recognize the diversity of their experiences, needs, and aspirations, particularly in terms of mobility. Refugees come from various cultural backgrounds, and these cultural nuances significantly influence their perspectives on and preferences for mobility. Moreover, different weather conditions and landscapes in their host countries play a pivotal role in shaping the modes of mobility that are viable and practical. Harsh desert conditions might need different transportation solutions compared to more temperate climates. Additionally, the availability of resources, both within the refugee camps and in the surrounding areas, significantly impacts the options for mobility. Considering these contextual factors is essential that solutions are tailored to be both practical but also culturally sensitive, considering the unique circumstances and preferences of the individuals within the residing community.

Between two households at the outskirts of the Wilaya Ausred. © Emma Lehbib

In Sahrawi refugee camps, mobility is not merely a convenience; it is a lifeline. It ensures access to resources, economic opportunities, education, healthcare, and community connections. For displaced individuals like Aisha, mobility fosters a sense of normalcy, autonomy, and empowerment, crucial for overcoming trauma and rebuilding lives.

“For me, [mobility] is important to work in order to facilitate my programs, even within the Wilaya. Most of the time, I use walking and frequent stops at the transportation stations which can be tiring and arduous, still, it is very important in my work. There is a possibility that one day I will own a car of my own.”

Aisha Alien

About the author

Emma Lehbib dedicates her time to an NGO and civil-society organization, focusing on the cause of Western Sahara, often referred to as Africa’s last colony — a cause tied to her roots. Regular visits to refugee camps, where her family resides, fuel her commitment to the right of self-determination of the Sahrawi people. Emma is a graduate in International and European Law from the University of Groningen, where she explored the legality of renewable energy projects in the occupied part of Western Sahara. During her internship at GIZ, she engaged in research on mobility issues within refugee camps, particularly focusing on the Sahrawi camps

Edited by Keisha Alena Mayuga and Ariadne Baskin.